最後更新日: 2024年06月28日

Welcome! This is the third installment of our interview series “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?”

“Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?” is an interview series with the aim to ask top economists a very important question: “Why haven’t economists come up with a new General Theory that can explain the Great Recession?” The question is not why we haven’t seen a resurgence of old-style Keynesian economics, but rather an inquiry into how the macroeconomics academia changed since the Great Recession, and more importantly, why the responses from macroeconomists nowadays are different from their counterpart in the 1930s.

In the third installment, we talked to Professor John Cochrane, Senior Fellow of Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He is famous for his research in Finance, Monetary policy and the Fiscal Theory of Price Level. His publications include one of the most widely used Finance textbook – Asset Pricing. His blog, “The Grumpy Economist”, is also one of the most influential economics blogs.

In this interview, Prof. Cochrane discusses with us his view on the development in Macroeconomics since the Great Depression. He also explains what Neo-Fisherian and Fiscal Theory of Price Level are, and why they are important for understanding the current economic situation around the world.

For more “Where is the General Theory of the 21st Century?“, please follow our series via RSS or our twitter handle @Keynes2016

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. All mistakes and miscommunications are ours.

Q: Econreporter C: John Cochrane

Q: Do you think there is a “New General Theory” emerging since the Great Recession? Where do you think Macroeconomics is heading now?

C: Eighty years ago, the General Theory inaugurated a very simple view of recession. There is only one element — lack of demand. It doesn’t really matter where does the lack of demand come from. Just like there is not enough water in the pool, you fill it up with more demand. There is just a single thing wrong with the economy — not enough demand, and there is just a single dimension of cure — stimulate demand. You can interchange monetary and fiscal stimulus. That’s a beautiful, simple view of the world, very easy to understand. All of the complexity of the economy stay away, all you need is just more demand.

Medicine, in the 18th Century, had the theory of four of humor. It was very simple, everything wrong in the human body came downs to not enough of the four things. Similarly, in the view of Keynesian economics, everything come down to this one thing, which is more or less demand. That is an unbelievably simplified view of how the economy works. What come in its way, like in modern medicine, is that there is not a single thing you can say things like “Aha! You need more Zinc in your diet and that will cure all your diseases!” We now understand that there are thousands of diseases, each with its own cure.

What’s wrong with the economy now is that there are a thousand things going wrong. Every market is screwed up in its own way. If we were having slow growth, that could be explained by growth theory, not just macroeconomics. The government interfered in the taxi market and slowed it down. The government interfered in the development of new drugs and slowed that market down. There is no single thing wrong that you can come in and say “Aha! We will have a stimulus program and solve it all!” You have to cure it the way you cure diseases.

I think the difference between microeconomics, macroeconomics and growth theory will disappear, but that would require much more new theories. If we have to help an addict living in a house full of big mess, old fashion demand-side macroeconomics would say: “Just forget that the house is a mess! All you need is a magic 10-day cure, then everything will be fine!” No, I am sorry! You got to diet, got to eat right, got to clean up the house.

Q: Do you agree that all the major macroeconomics trends emerged after the Great Recession are mostly just reboots of the old ideas?

C: I think you got the observation quite right. Almost all economists, both in finance and macroeconomics, say right after the financial crisis and Great Recession: “Hey look! We have a financial crisis and a Great Recession, that proved I was right all along!”

Yet, I would say this is actually a right approach to problems. If economics is a discipline where every data point requires a brand new theory, that’s not much of a discipline. When Physics see something new in the sky, they tend to not say: “Hey, Einstein was wrong! We have to start from scratch!” The first thing you do is try to fit the new phenomenon in with the theory you already have. I don’t think most of what we have seen, for example, the fact of the financial crisis and slow growth, those are not facts that demand a particularly new theory, as we have so many theories already.

The events we have seen have been quite similar to events we have seen in the past. We have financial crises on and off since 1700. At its core, this financial crisis was a run, just like many other financial crises. I think that is the most productive way to approach the financial crisis. Similarly, we are having a period of very slow growth, let’s blame over-regulation and an economy that has too much sand in its gears. Just apply what we got off the shelf and it seems to fit pretty well.

Q: Let’s go back to your Medicine analogy, I would say macroeconomics doesn’t has its Germ Theory. For example, I think we don’t really have a consensus view on what caused the financial crisis.

C: Why did there a sharp recession after the financial crisis? I don’t think this is a difficult problem. Lack of aggregate demand, though vastly oversimplified, does explain why we have a sharp recession after the financial crisis. The puzzle is why we didn’t grow quickly afterward.

Almost all economics, Keynesian, Monetarist and all the official forecast said in 2008 that after the recession, we will have a very quick bounce back, just as we did in the early 1980s. Once the banks were settled in March of 2009, everybody thought: “Good, we will bounce back up to where we were!” The puzzle is we never actually bounce back.

I think that this illuminates theories. The theory that bites the dust here is traditional Keynesian. It makes explicit predictions that just failed pretty dramatically in the last 8 years.

Q: You have mentioned the puzzle of slow growth, I think this is a good entry point for our discussion of Neo-Fisherian view of inflation. One of the issues suggested by the Neo-Fisherian, I guess, is that the Fed should not keep the interest rate this low, am I right?

C: Well, let’s separate the question of “how did the economy work” from “what should the Fed do”.

Everybody used to complain about it. But when you think about it, zero percent interest and deflation is actually perfect monetary policy. This is the idea of Milton Friedman from a long time ago. If the interest rate is zero, you get your rate of return from the slight deflation. That is just about perfect.

Let’s think of some of the reason why. Normally, the interest rate is higher, and you have to spend a lot of time making sure you don’t have cash lying around. You have to do a lot of cash management, making sure everything is in your bank account, earning interest all the time. If somebody owes you money, you have to make sure that you collect that bill quickly before you lose interest on it.

At zero percent interest rate, who cares? Cash lying around is just fine. Furthermore, the US and most other countries charge taxes on interest, which is a bad idea. It is an important tax distortion, encouraging a lot of stuff goes on to try to avoid the tax. If we are not paying interest, then there are no taxes on interest. That’s wonderful too.

Your presumption is that there is something bad with it, and the central bank should raise the interest rate and raise inflation. I am not so sure that is right. I am kind of happy where the things are.

So what is the Neo-Fisherian idea? We take for granted that if the central bank raises the interest rate, that lowers inflation. That’s kind of a common thing everybody said. But let’s look at what happened over the last number of years. Central banks set interest rates to zero, what happened to inflation? Inflation slowly declines, back down towards where the interest rates are. Boy! Doesn’t it look a lot like if the central bank lower interest rate, that lowers inflations? In fact, that’s always been the long-run view, the question has always been the short-run.

The standard view is that the central bank is controlling the interest rate the way you would balance a broom on its head. It’s unstable, so you always have to move the interest rate around to keep the inflation rate in check. If you move the bottom of the broom one way, top of the broom falls off the other way. Once the rate hit zero, the Fed can’t move interest rate. Inflation should have toppled.

The Keynesian say we will have a deflation spiral. They are exactly right to predict that as that’s what their model said. The Monetarist say we are gonna have hyperinflation. Again, they are exactly right to predict that as that’s what their model said. But we have nothing. The interest rate is zero and inflation is just very quietly doing nothing.

I call this the Michelson–Morley moment. It’s a very famous experiment in Physics that proved there was no aether. The fact that nothing happened and all of the models predicted an explosion, I think is very revealing, suggesting that if the central bank hold interest rate steady, inflation will eventually settle down where the interest rates are, not the other way around. That’s the core of the Neo-Fisherian idea.

Q: So the Neo-Fisherian view suggests that, if the central bank pegs the interest rate, the inflation rate will be stabilized?

C: Yes, but with a big asterisk. If you look at the last 8 years of the US, Japan, and Europe, it certainly looks that way. The interest rate is zero, inflation is very stable. We have more stable inflation in the last 8 years than we have in pretty much ever.

Now, let me explain the asterisk. The asterisk is fiscal policy and the fiscal theory of price level (FTPL). We have now observed the period of fixed interest rate and stable inflation, but that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, the traditional view came from many experiences. When countries set a low-interest rate, inflation explodes. What’s up with that?

That’s where Neo-Fisherian and FTPL kind of come together. When we look at those episodes, when the central banks try to lower inflation by lower interest rate, those are all episodes where the governments were in deep fiscal problems. They were borrowing a lot of money, spending too much, didn’t have enough taxes. They were using monetary policy to try to cover things up. In order for lowering interest rate to lower inflation, you need people to trust the government’s fiscal policy. If people don’t trust the government’s fiscal policy, then it’s not gonna work. There are not many things the central banks can do about inflation.

What is Fiscal Theory of Price Level?

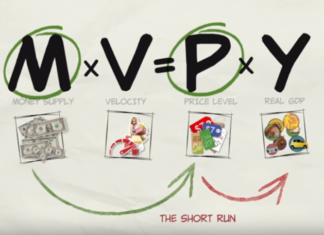

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level says that money has value because the government accepts it for taxes, and inflation is fundamentally a fiscal phenomenon. It can also be viewed as a model of monetary–fiscal policy coordination. The equation of the FTPL is as follow:

where real debt (which is nominal debt divided by the price level) is always equal to the present value of all the future real primary surplus of the government. According to this theory, the price level of a country should rise with the level of nominal debt of the government, the discount rate of government debts, or a fall in future real primary surplus, hold other things constant.

Q: In your recent paper “Do Higher Interest Rates Raise or Lower Inflation?“, the discussion about the Neo-Fisherian view is rather theoretical. Is there any other historical episode that supports the Neo-Fisherian analysis? Or is it just most an argument based mostly on the theoretical ground?

C: I am still revising the paper you have just mentioned and hope it will be better soon. But it is theoretical for a reason.

We know all economic theories and experiences suggested that in the long run, a higher interest rate goes with higher inflation. The question is what happens in the short run. Is it possible that if we raise the interest rate, there is a short run where inflation goes the wrong way, and then it comes around the right way eventually? That’s the question that I don’t know the answer to.

So one thing you can do is to try to look at empirical evidence, which is difficult. The point of that paper was to look around and say, “what do modern theories say about this question?” That was important because when we teach in undergraduate class, everybody teaches that if the Fed raises the interest rate, that would lower the inflation for a little while, then eventually it will turn around.

Is there a modern theory that actually make that prediction? The answer seems to be no! It was important. I was actually quite surprised to find that when you look at the equations of modern theories, modern theories say raise interest rate immediately raise the interest rate. Even though we teach that in undergrad, it turns out modern theories don’t say that raising interest rate lower inflation for a while.

Q: From your literature review, I understand that there were other researchers pointed this out, why hadn’t these analyses go into mainstream economics?

C: Our central bankers operate with about a mid-1970s ISLM view of the world. In that view, it is true that raising interest rate lowers inflation. It does so permanently. In that view, the economy is unstable, like the upside down broomstick. But that view also has kind of been thrown out both theoretically and empirically. It relies on people being stupid, as if they are always driving while looking in the rear mirror, and the central bank need to push them back on course.

So what I meant modern theory is theories that respectable economics theory that we have been using since the 1980s. What do they predict? It turns out they predict the Neo-Fisherian result. I am still looking for one that produce what everybody thinks that is true, so we will see how does that come out.

Q: Are there any other historical episodes that suggest the Neo-Fisherian view is right?

C: In the post-WWII era, the US pegged the interest rate. Starting in about the 1940s the US central bank simply said, “the interest rate on long-term government debt is gonna be two percent, period.” That lasted from the 1940s to the mid-1950s. Interestingly, it fell apart on the fiscal pressure on the Korean War. So one way to read that episode is a successful peg that then fell apart when fiscal policy wasn’t enough to take care of it.

Another important episode in monetary economics is the end of hyperinflation. For example, Tom Sargent wrote the most classic paper “The Ends of Four Big Inflations” on this. Germany after the WWI had a huge hyperinflation. The reason they had hyperinflation is they had to pay reparation under the Treaty of Versailles, and they weren’t able to do it, so they were basically printing up money to pay government’s bills. Printing up money to pay the fiscal deficit, that causes huge inflation.

So what stopped the inflation? What stopped the inflation is not the central bank monkeying around with interest rate, or even money supply. What stopped the inflation was that they came to an agreement that solved the fiscal problem, that made the government able to pay its bill. Then the inflation stopped essentially overnight, interest rate fell immediately, and the money supply grew because people were more willing to hold German marks, and the central bank was able to print lots more. So think about this, if you just look at the date, what you see is when inflation stopped, interest rate go down uniformly, no period of high-interest rate to remove the inflation, and the money supply grow. That look really strange from standard monetary views that said you need to shrink the money supply or raise the interest rate to get rid of inflation. But exactly the opposite happened. So that’s a nice example either for FTPL or Neo-Fisherian.

Another important episode is the late 1800s, under the gold standard the world had 20-30 years of very very low-interest rate and slight deflation. There was a nice period of robust economic growth and deflation.

The Great Depression is also another example. The Great Depression was terrible for all sorts of reasons, but the interest rate was zero. And there weren’t a whole lot of inflation.

Q: Surgent had developed this theory for more than 30 years, what it hasn’t been adopted in the mainstream? What has changed lately?

C: Actually, FTPL has a much deeper origin. Adam Smith had a gorgeous quote:

“A prince who should enact that a certain proportion of his taxes should be paid in a paper money of a certain kind might thereby give a certain value to this paper money.” (Wealth of Nations, Book II)

So the basic idea is right there in Adam Smith.

The puzzle of all monetary economics is “why do we work so hard for this pieces of paper?” When you think about it, it’s really puzzling. You and I go out and sweat hard all day, what do we take home? Some pieces of paper with a picture of dead presidents on them. Why do we work so hard for these little pieces of paper? Well, because we know somebody else will take them. But why does somebody else take them? That’s the puzzle of economics.

The FTPL answers that puzzle at a deep level. Here is why — because in the US you have to pay taxes every April 15. And you have to pay taxes with that same government money. In the old day, you give them the sheep and the goats, but they won’t take that anymore. They want their paper money back. So fundamentally, the value of money comes from the government’s willingness to take it for taxes.

Sargent’s work was just absolutely breathtaking in showing that. But Milton Friedman also wrote a famous paper on the coordination of monetary and fiscal policy. So at a level, the theory is been around a long time. The question is just the emphasis.

Sargent and Wallace show that to understand those historical episodes, the end of inflation is not just the central bank being tough enough, but it was actually about how to cure a fiscal problem, as the government is printing up money and not soaking enough in taxes.

The FTPL since Surgent and Wallace has taken a lot of development. Working out how these work just take a lot of work. Then figuring out how to apply it to data is not easy either. For example, how do we understand Japan? This is the standard question when I talk about fiscal theory. Two hundred percent debt to GDP ratio and keep borrowing money, yet there is still no inflation. So how do we make sense of that with this underlying theory? We can do it, it is just not so obvious how to bring any simple sounding theories to data and how to elaborate. That’s the works we are doing, and there are a lot more to do.

Q: Do you think that this is the best time for FTPL?

C: Well, this is my pet project that I have been working on for 30 years, so I think anytime is the right time. Haha~

I think a good theory like this ought to be consistent with every data it is out there. I just feel I am particularly lucky that we have, sitting in front of us such a piece of evidence. The stability of inflation at zero interest rate just demolished the competing theories. The FTPL isn’t easy, but it’s the only one standing. So yes! I think it’s time. But I would think it’s time no matter what is happening. Haha~

(The conversation continues in Part II)

本網內容全數由Patreon嘅讀者贊助

如果你都鐘意我地嘅文章,可以考慮成為我地最新嘅Sponsor !

想睇到我地最新嘅文章,可以去Telegram follow 我地 詳見《Econ記者使用說明》